The Menu Bar, HyperCard, the Double-Click

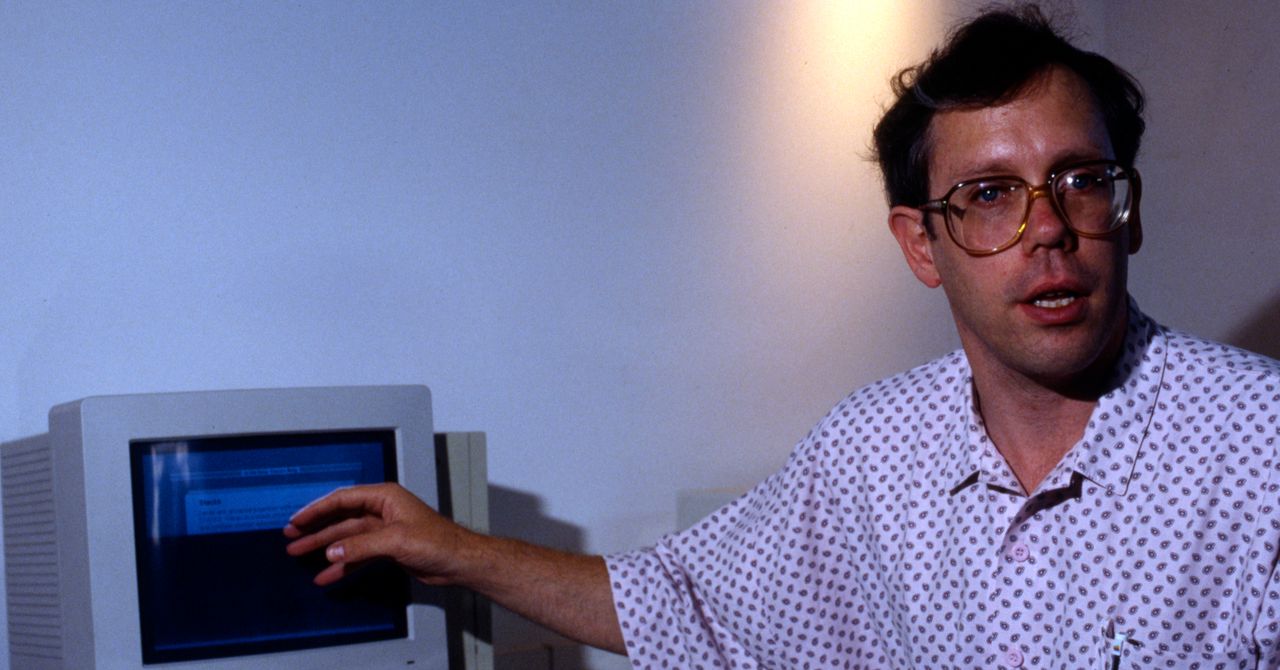

With the news of the passing of Bill Atkinson a few days ago, I've been drawn down some truly and insanely great rabbit holes of information and fun clips about the man who invented so much of the computing we now take for granted today.

Atkinson hadn’t planned on becoming a pioneer in personal computing. As a graduate student, he studied computer science and neurobiology at the University of Washington. But when he encountered an Apple II in 1977, he fell in love, and went to work for the company that built it a year later. He was employee number 51. In 1979, he was among the small group that Steve Jobs led to the Xerox PARC research lab and was blown away by the graphic computer interface he saw there. It became his job to translate that futuristic technology to the consumer, working on Apple’s Lisa project. In the process, he invented many of the conventions that still persist on today’s computers, like menu bars.

Those menu bars may or may not be on the verge of getting – yet another – coat of new paint tomorrow at WWDC, but you can bet they'll still be there, strikingly similar to the ones Atkinson created all those decades ago.

When Jobs took over the other Apple project inspired by PARC technology, the Macintosh, he poached Atkinson, whose work had already influenced that product. Hertzfeld, who was in charge of the Mac interface, once explained to me the Lisa features he’d appropriated for the Mac: “Anything Bill Atkinson did, I took, and nothing else.” he said. Atkinson, who had become disenchanted at the Lisa’s high price tag, embraced the idea of a more affordable version, and began writing MacPaint, the program that would empower users to create art on the Mac’s bit-mapped screen.

Speaking of Hertzfeld, on his site, Folklore, Atkinson has a few posts about his memories of his days at Apple – such as the day he joined in 1979:

I don't know what Jef told Steve Jobs about me, but Steve spent the entire day recruiting me. He introduced me to all 30 employees at Apple Computer. They seemed intelligent and passionate, and looked like they were having fun, but that was not enough to lure me away from my graduate studies.

Toward the end of the day, Steve took me aside and told me that any hot new technology I read about was actually two years old. "There is a lag time between when someting is invented, and when it is available to the public. If you want to make a difference in the world, you have to be ahead of that lag time. Come to Apple where you can invent the future and change millions of people's lives."

Then he gave me a visual: "Think how fun it is to surf on the front edge of a wave, and how not-fun to dog paddle on the tail edge of the same wave." That image persuaded me, and within two weeks I had quit my graduate program, moved to Silicon Valley, and was working at Apple Computer. I never finished my neuroscience degree, and my dad was mad at me for wasting ten years of college education that he helped to pay for. I was pretty nervous, but knew I had made the right choice.

The "Do you want to sell sugar water for the rest of your life or come with me and change the world?" Steve Jobs pitch to recruit John Sculley to become the CEO of Apple is the far more famous example of the same general idea. Clearly, it's one that worked for Jobs quite often from nearly day one...

Another massively profound change in computing that Atkinson seemingly gets no credit for but impacts every single person on the planet:

The Apple II displayed white text on a black background. I argued that to do graphics properly we had to switch to a white background like paper. It works fine to invert text when printing, but it would not work for a photo to be printed in negative. The Lisa hardware team complained the screen would flicker too much, and they would need faster refresh with more expensive RAM to prevent smearing when scrolling. Steve listened to all the pros and cons then sided with a white background for the sake of graphics.

Can you imagine if we all still used computers where black backgrounds were the norm? The world would literally be a far darker place. I still recall what this was like using DOS as a kid (and Apple IIs at school). It just felt like a colder form of computing.

Back to Steven Levy:

After the Mac launched, the team began to unravel. Atkinson had the title of Apple Fellow, which gave him the freedom to pursue passion projects. He began work on something he called Magic Slate—a device with a high-resolution screen that weighed under a pound and could be controlled by a stylus and swipes on a touch screen. Basically, he was designing the iPad 25 years early. But the technology wasn’t ready to create something so miniaturized and powerful at an affordable price (Atkinson hoped it would be so inexpensive you could afford to lose six in a year and not be bothered.) “I wanted Magic Slate so bad I could taste it,” he once told me.

Just imagine trying to create the iPad in the 1980s. The "portable" computers back then weighed 20 to 30 pounds!

After the failure of Magic Slate, Atkinson fell into a months-long depression, too disheartened to turn on his computer. One night, he took LSD and wandered out of his home in the Los Gatos hills. Staring into the vast collections of pixels that made up the night sky, he became reenergized, and decided to adopt some of the Magic Slate ideas into software that could run on the Mac.

He designed a program where information—text, video, audio—would be stored on virtual cards. These would link to each other. It was a vision that harkened back to a 1940s idea by scientist Vannevar Bush which had been sharpened by a technologist named Ted Nelson, who called the linking technique “hypertext.” But it was Atkinson who made the software work for a popular computer. When he showed the program, called HyperCard, to Apple CEO John Sculley, the executive was blown away, and asked Atkinson what he wanted for it. “I want it to ship,” Atkinson said. Sculley agreed to put it on every computer. HyperCard would become a forerunner of the World Wide Web, proof of the viability of the hyperlinking concept.

Yes, he more or less laid the framework for the web – while on LSD. From there, it was off to help found General Magic, the too-early device company that created concepts for what would eventually become things like the iPod and iPhone.

I'll end with an excerpt from John Markoff's write-up on Atkinson's passing for The New York Times:

Mr. Atkinson’s programming feats were renowned in Silicon Valley. “Looking at his code was like looking at the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel,” recalled Steve Perlman, who as a young Apple hardware engineer took advantage of Mr. Atkinson’s software to design the first color Macintosh. “His code was remarkable. It is what made the Macintosh possible.”

One more thing: back to the GUI:

Mr. Atkinson is credited with inventing many of the key aspects of graphical computing, such as “pull down” menus and the “double-click” gesture, which allows users to open files, folders and applications by clicking a mouse button twice in succession.